How a simple mathematical game offers some surprising insights into deeper questions

Was life created, or does it evolve? Is God responsible for life, or did it all just happen? When a friend and I were discussing these questions a while ago, he mentioned the mathematical Game of Life, offering it as an example of how complex systems can evolve — be born, live, and die. To him this demonstrates there’s no need to believe in a “God” to explain the existence of life — it’s all just evolution.

This piqued my interest since mathematics has always been a reliable companion. Sure enough, the Game of Life did not disappoint. It was created in 1970 by John H. Conway, a British mathematician. Its very simple rules lead to a wide variety of behaviors that arguably imitate life. Originally, the game was played on graph paper grid or a Go board, and soon thereafter on computers.

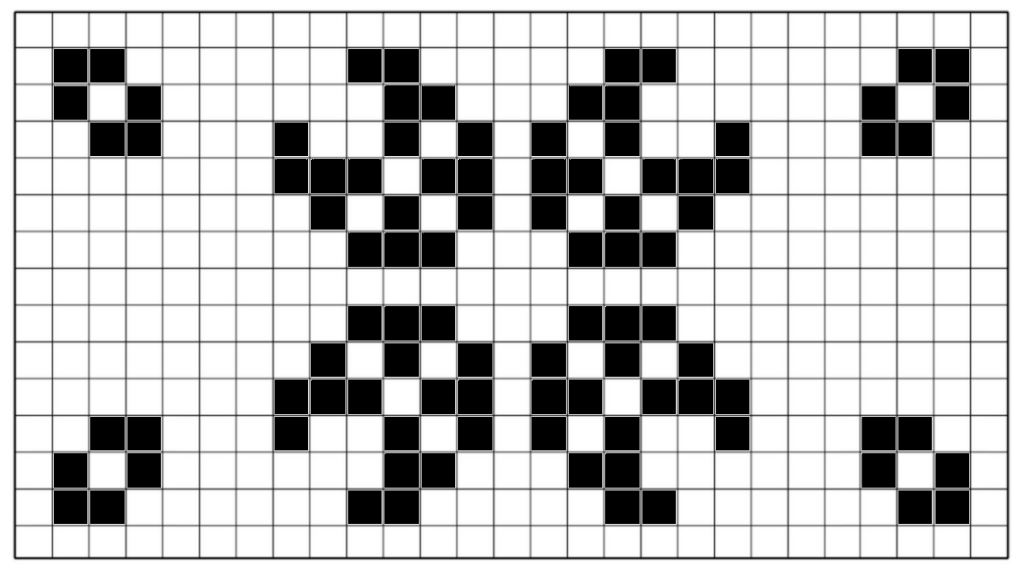

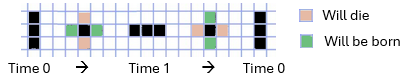

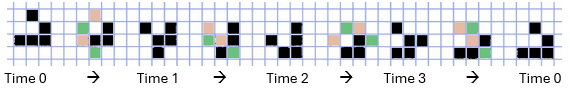

The idea is that the grid is made up of dead (white) cells, and live (black) cells. You start with a colony of several neighboring live cells, and from there the life of the colony evolves according to rules, but often in unpredictable ways. Time is marked by ticks of a clock. At each tick, the number and placement of the next generation are determined by these four rules:

- Any living cell with two or three neighbors stays alive, being well-supported. (A neighbor is any adjacent living cell, including diagonally.)

- Any living cell with less than two neighbors dies off from isolation.

- Any living cell with more than three live neighbors dies off from overcrowding.

- Any non-living cell neighboring exactly three living cells is born and becomes alive.

From these simple rules and some initial configurations, an enormous variety of colonies can grow, shrink, and sometimes even move across the grid in fascinating patterns. Please see this article for details.

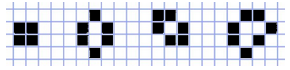

Four types of colonies survive indefinitely:

- Still life — no births or deaths, it just stays the same.

- Oscillator — changes configuration one or more times, always returning to the exact original.

- Glider or spaceship — an oscillator that moves across the grid each full oscillation.

- Gun — generates new colonies, typically gliders.

Other patterns may not repeat, but some can survive for hundreds of generations before finally dying off.

Is it life?

When you see a computer animation of the game, the colonies sure look alive. They grow, mutate, move, and often die. They exhibit qualities of emergence, in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. They also seem capable of self-organization, the spontaneous formation of patterns in space, over time, without external intervention.

In his book, The Seven Mysteries of Life, Guy Murchie has identified seven characteristics of life that might apply here:

Abstraction — in which life is understood to be a wave of higher-level order that passes through an environment of lower-level order. This seems to be the case here, as the “living” cells exhibit orderly change on the inert background of the grid.

Interdependence — where each life form depends on other life forms. This has been designed into the Game of Life, in the four basic rules, where survival depends on neighboring cells.

Omnipresence — states life can be found everywhere. To make this claim, Murchie takes a very broad view of what life is. Within the Game of Life this could apply, since a colony can exist anywhere on the grid.

Polarity — has to do with the inherent opposites of life, such as birth and death, or predator and prey. Again, birth and death are designed into the game.

Transcendence — is related to the concept of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. In the Game of Life, at the individual level, the cells are either born, living, or dead. But together they make up a colony. Watching a complex oscillator, it seems like a living being that transcends the individual cells, moving and transforming itself.

The Germination of Worlds — looks at how a stable system may receive a sudden impetus to germinate, such as a seed exposed to moisture. This moment, as I see it, happens in the Game of Life when someone sets up an original configuration. After that, the thing goes and grows by itself.

Divinity — observing that the universe has order and embodies intelligence, Murchie finds the most reasonable explanation to be a Creator. Some may question the validity of such an idea, but one thing is certain: the Game of Life had a creator.

Murhcie’s mysteries alone do not give us a complete definition of life. For example, they do not mention specific biological processes like homeostasis, metabolism, or reproduction. But, allowing for the simplicity of the game, you could assert that it includes these characteristics of life as well. Each living cell maintains itself until it dies, which is arguably homeostasis. And in a sense, the cells metabolize the energy of the computer or game player when they are created. And finally, although it takes three cells to give birth, there is a form of reproduction.

Beyond the creation/evolution dichotomy

Once I became familiar with the Game of Life, I began wondering why my friend chose it to support his atheistic claims. To me, it suggested something far more. It sheds light on the old creation vs. evolution dichotomy. For decades people have been asking whether life evolved or if it was created in a few days, as implied by a literal reading of the Bible. Looking at the Game of Life suggests the story may be more sophisticated, as well as more satisfying.

Let’s start with the physical infrastructure. The game is typically played on graph paper, a Go board, or a computer screen. Were they created, or did they evolve? Actually, they were pre-existent to the game, even to the idea of the game. At a higher level of abstraction, space and time also existed before the game was invented. So however the game came into being, it did so within the framework of a broader, more inclusive reality.

Next, consider the energy the game needs to perform its magic. It can be human energy — someone filling in graph paper squares or flipping Go tokens. Or it can be electrical, powered by computer. Either way, where is the source of that power? Clearly outside the game. Was it created, or did it spontaneously evolve? No matter how hard you study the game, you won’t find the answer within its universe. The energy comes from outside.

Moving up to yet higher levels of abstraction, how about the absolute necessity of rules of the game? They weren’t obvious. In a video interview Conway says “For about 18 months of coffee times… we tinkered with the rules…and finally came up with the ones I said.” (See above.) These rules are arguably the essence of the game.

Will and purpose

Could there be anything else? Well, what about the idea of having a game in the first place? What was the point of it all? It seems Conway had a purpose. He had intention. He continues, “And they [the rules] really seemed to have very nice properties, namely you didn’t seem to be able to predict what would happen.”

So, the game was designed with purpose — an intention to include a measure of unpredictability. And indeed it does. Some of the most interesting features of the game were not predicted at the start. Many combinations, including gliders, were only discovered after months or years of people playing it.

This element of intention, of purpose, suggests will, the will of the creator. The source of that will is also far beyond the confines of the game, and yet, it is evident in the game. In this sense, the Game of Life embodies and expresses the will of its creator.

Does it apply?

So, what do you think? Does this simple-looking game give us any insights into our lives, into life itself? Does it shed light on the creation vs. evolution question? Can it help us see beyond it?

Our universe is far more diverse than a two-dimensional grid. Microorganisms, plants, animals, and ourselves are far more complex than filled-in boxes. Yet it took time, effort, and thought by a noteworthy mathematician to come up with four basic rules that yield something resembling life on that grid. Carrying out the idea required resources completely beyond the awareness of any cell in the game, were it capable of sensory perception and reason.

We who do have perception and reason look around at our own world and its abundant variety of life forms, and might wonder if there is anything beyond what we see. For me, the answer is clear. If so many resources outside the Game of Life were needed to create it, and are used to run it, why should our world be any different? There could be more upholding our reality than we perceive.

Eternal Life

There was a time when the Game of Life did not exist. Then it was created. And now, in a sense, it is eternal. If you destroy all the Go boards, shred all the graph paper, delete all the programs, and even take a sledgehammer to all the computers in the world, the Game of Life will remain as long as the idea is there. The four rules will still hold if anyone knows them and can apply them. Whenever or wherever someone finds a grid of square cells that support binary coloring, creates a few seed cells, and supplies the power to run it, the rules can be applied, and the game is on. Colonies will flourish, gliders will glide, oscillators will oscillate, and still life will stay put.

And how about us? There is so much more defining our existence than four mathematical laws. Of course, we are physical beings and our bodies will die and eventually decompose. But beyond that, we have hopes and dreams, experience and wisdom. We have built character. We have woven bonds of love between ourselves and perhaps a higher power. If we know ourselves to be creatures of an eternal, all-knowing Creator, will He not remember us? After we put away this mortal frame, shall we not also continue in the abstract, eternal dominions, the all-embracing realms of spirit?

“O son, if thou art able not to sleep, then thou art able not to die. And if thou art able not to waken after sleep, then thou shalt be able not to rise after death.” [1]

Notes

- Attributed to the ancient fabulist and philosopher Luqmán on page 44 of The Call of the Divine Beloved, by Bahá’u’lláh, Founder of the Bahá’í Faith.

Originally published by Brain Labs on Medium